The popularity of the Japanese manga “Haikyu!!” has led to the happy consequence of widely familiarizing many people with previously lesser-known volleyball terminology.

Having a common language of volleyball terms allows us to think and discuss the sport together, which is essential for its development.

While I am delighted that so many volleyball terms are becoming widespread through “Haikyu!!”, looking at some of these terms, I realize that my own understanding, or “resolution,” of them is often not high enough. Moving beyond merely knowing the words to truly understanding their core concepts is a critical step for comprehending modern volleyball.

Ultimately, this enhanced understanding could become a major driving force in shaping the future of the sport.

This article focuses on two terms whose recognition and interpretation often seem ambiguous among people, starting with a deep dive into one: ‘Tempo.’

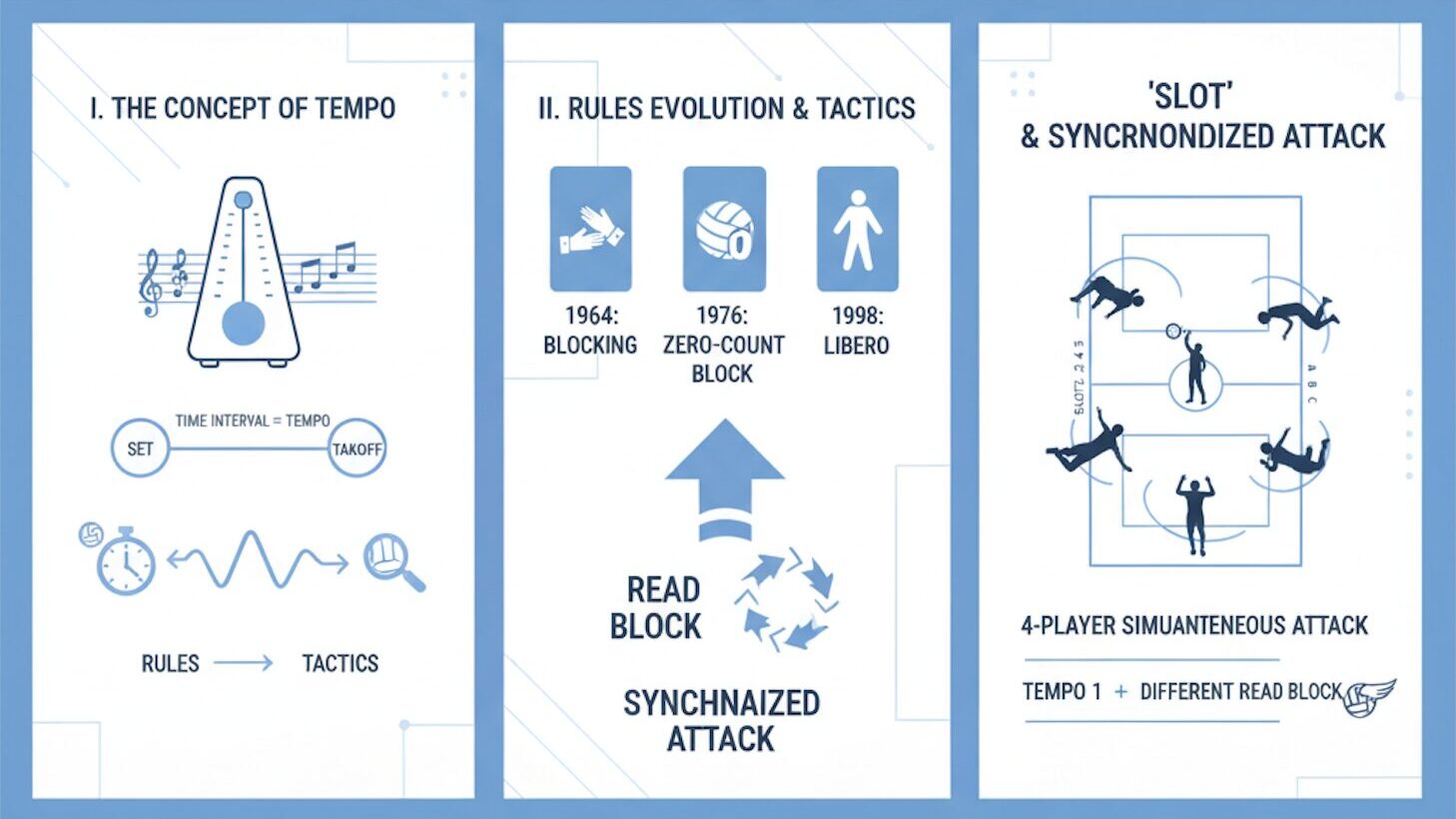

- The Concept of ‘Tempo’

- The Relationship Between Rules and Tactics

- Rules Give Birth to Tactics

- Rule Changes That Transformed Blocking and Attacking

- How Read Block Tactics Gave Birth to Tempo

- The Rise of the Read Block

- Tactics Give Birth to New Tactics

- ‘Tempo’ and ‘Slot’

- Synchronized Attack: The Counter-Tactic

- Lessons Learned from the Concept of Tempo

The Concept of ‘Tempo’

Where does the term ‘tempo’ originally come from?

Driven by curiosity, I looked into its etymology and found its origins lie in Italian. (The word ‘tempo’ immediately brings a metronome to mind.) Since music and sport are related (in terms of enjoyment), there’s a certain affinity between them.

The essence of tempo is “time.” More specifically, in the context of music, it refers to the time interval connecting two points.

The Tempo of Music

What I found most fascinating was that, originally, there was only one tempo, which naturally corresponded to the human pulse (60 to 80 beats per minute). This suggests that music emerged organically.

Yet, humans are restless creatures.

Composers were not content with this one natural tempo and went on to create new, “artificial” tempos, giving them sophisticated names (e.g., adagio, allegro, presto). The invention of the metronome in the 18th century provided a precise way to measure these speeds (e.g., $quarter-note = 72$). Thus, the concept of tempo was rigorously established in the world of music.

Conversely, the fact that the concept of tempo did not spread similarly in non-Western countries is highly intriguing. While Western music systematically defined and quantified tempo in a common and measurable way, non-Western music often relied on oral tradition, lacking a corresponding, quantitatively defined concept of tempo.

This suggests a fundamental difference:

- Western music moved towards an open-source culture, actively defining and documenting musical speed with terms and tools (metronomes) to rationally and widely disseminate knowledge and build upon it.

- Non-Western music often maintained a closed-source culture, with knowledge transmission limited to specific individuals through oral tradition, restricting the spread and formal definition of concepts like tempo.

It can be argued that this open-source approach to concepts like tempo allowed Western music to achieve explosive global development.

While reflecting on the history of tempo in music, I couldn’t help but feel: Doesn’t the concept of tempo and its historical changes in the volleyball world share some parallels? Although a detailed comparison would require its own article, this realization highlights the importance of understanding a term’s historical context.

The Relationship Between Rules and Tactics

Now, let’s turn to the concept of tempo in volleyball.

How did it emerge and spread? To answer this, we must consider two essential keywords: ‘Rules’ and ‘Tactics.’

Rules Give Birth to Tactics

Rules are the unique existence that make volleyball, well, volleyball (the word “rule” as a verb means “to govern”). Even when the sport was first created by William G. Morgan, the initial rules were established through vigorous debate.

However, as the sport spread globally, new questions and ideas arose: “Is this permitted by the rules?” “Wouldn’t changing this rule make the game more interesting?”

As a result, special rules began to emerge in specific countries or regions—for example, the 9-Player Volleyball format still popular in Japan.

While special rules are fine for local enjoyment, a world standard rule becomes necessary when discussing international competition, such as the Olympics. The FIVB (Fédération Internationale de Volleyball) has historically led the charge in formulating and updating these global rules.

So, what emerged as a result of establishing world standard rules?

Tactics were born.

Under world standard rules, teams worldwide, driven by the natural desire to win the game, engaged in trial and error to create methods of play. It is crucial to emphasize that tactics were literally “born” from the rules. Rules and tactics have a parent-child relationship; Rules are the parent of Tactics. Understanding this relationship reveals that the historical changes in tactics are completely linked to the historical changes in rules. Without this understanding, even having a vast amount of tactical knowledge does not equate to true comprehension.

Rule Changes That Transformed Blocking and Attacking

The FIVB has updated the world standard rules numerous times to keep volleyball attractive.

Some changes have had a decisively large impact on tactics. Here are three major rule changes that significantly influenced blocking and attacking tactics, the two concepts most relevant to the birth of ‘Tempo.’ (Note: Blocking and attacking tactics are closely related and mutually interactive.)

1. 1964: Reaching beyond net to block permitted and multiple block contacts allowed.

This was revolutionary. Blocking, which was previously only a defensive play in the front zone, also gained an offensive role in the front zone. This shift immediately altered the power balance between offense and defense and spurred the creation of new blocking and attacking tactics.

2. 1976: Three ball system introduced and three hits after the block introduced to speed up game.

This change amplified the effect of the 1964 change, accelerating the development of block tactics. Crucially, the block contact ceased to be counted as the first hit (zero-count block), leading to major changes in defensive transition tactics (moving from digging to counter-attacking). This brought about a dramatic change in the offense/defense power balance.

3. 1998: The “libero,” a specialized defensive player, introduced to improve the “first pass” and defensive “dig pass.”

The Libero system dramatically enhanced back-zone defense. It improved the quality of the first ball during a positive transition, supporting the execution of more systematic and tactical transition attacks. This rule, too, was aimed at adjusting the offense/defense power balance, emphasizing the need to keep the rally going, which is volleyball’s greatest appeal.

How Read Block Tactics Gave Birth to Tempo

We can now finally discuss Tempo.

Having covered the relationship between rules and tactics, the reason for the birth of the Tempo concept becomes clear. This is because Tempo is an essential concept required to develop new tactics to counteract a specific, standard blocking tactic.

What is this specific tactic?

It is the Read Block tactic.

For readers familiar with the manga “Haikyu!!,” this term will be recognizable. Read blocking is now the standard blocking system at the world’s top level. A read block is executed by first observing (reading) the set ball’s trajectory and the attacker’s situation before stepping and jumping. The term is ‘read’ (to observe), not ‘lead’ (to be in front).

The Rise of the Read Block

Before the Read Block was developed, the dominant tactic was the Commit Block. A commit block involves the blocker stepping and jumping in sync with the attacker’s approach, committing one blocker to one attacker to stop the hit. In this era, where the three front-row players were the primary attackers, committing one blocker to one attacker was sufficient to prevent unblocked attacks. It was a one-on-one battle of individuals.

However, the dominance of the Commit Block began to crumble as attacking tactics like delayed attacks (time differential attacks) and the constant participation of back-row players (Back-Row Attacks) became standard, creating a numerical advantage for the offense. The individual-focused Commit Block tactic was no longer effective.

The Read Block tactic emerged to counter this offensive advantage. By confirming the trajectory of the set ball before stepping and jumping, the read block system theoretically allows the defense to deal with attacks by four players without giving up an unblocked hit.

Furthermore, with organized movement, blockers can achieve a numerical advantage (two or three blockers) against one hitter. This was a revolutionary tactic. The effectiveness of the Read Block was demonstrated by the US Men’s National Team, which adopted it and won two consecutive Olympic gold medals under Coach Doug Beal.

Tactics Give Birth to New Tactics

For readers who have persevered through this explanation, you now fully understand the saying: Tactics give birth to new tactics.

The Read Block is no longer a “new” tactic; it is the global standard.

When a new tactic becomes standardized, history shows what happens next: a new counter-tactic is born.

The Read Block tactic gave rise to the Synchronized Attack (Simultaneous Multi-Positional Attack) tactic.

Simply put, a synchronized attack is a tactic where four players (excluding the setter and Libero) attack simultaneously using the First Tempo (Tempo 1) from different Slots (spatial positions).

‘Tempo’ and ‘Slot’

The term ‘Tempo’ finally appears, accompanied by the concept of ‘Slot.’ Understanding both is essential for grasping the Synchronized Attack tactic.

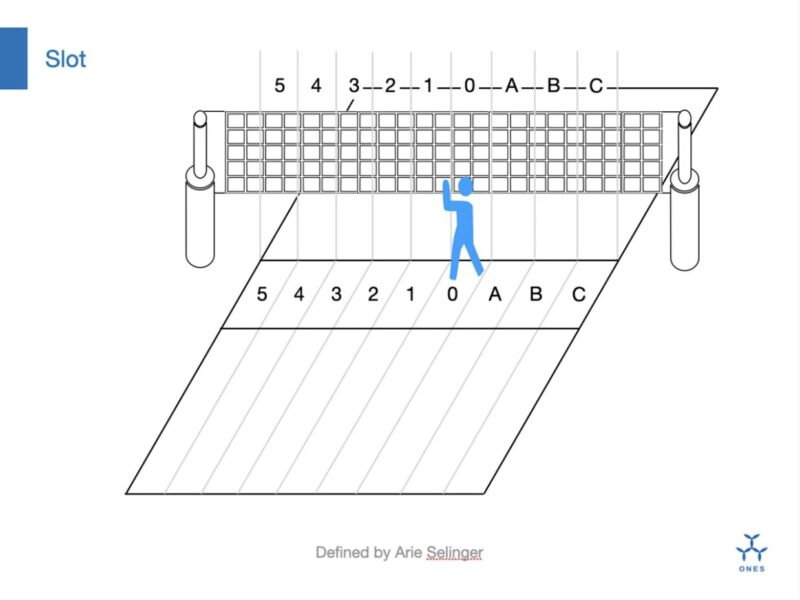

The Concept of Slot

The concept of ‘Slot’ is intuitively easier to grasp. In volleyball, the Slot refers to the spatial position from which an attacker hits the ball. More specifically, it often involves dividing the court width (9 meters) into segments using a horizontal coordinate axis parallel to the net, with numbers or symbols representing these spatial locations.

A common method, often referenced in Japan from the book Selinger’s Power Volleyball, defines the setting point as Slot 0, with Slots 1–5 set towards the left side and Slots A–C towards the right side.

The Slot concept allows for efficient and precise tactical discussion—moving beyond vague spatial references like “left, center, right”—by clearly defining which attacker participates from which specific spatial location. With the Slot concept shared, understanding the Synchronized Attack is halfway complete.

The Nuance of Tempo

Tempo is trickier than Slot. As established earlier, the essence of tempo is time—the duration of the time interval connecting two points.

In volleyball terminology, Tempo is determined by the length of the time interval between the moment of the ‘Set’ and the moment of the ‘Takeoff’ (jump).

We will now examine the four types of Tempo using the framework of the time elapsed between the Start of Approach, the Set, and the Takeoff.

Tempo Types and Characteristics

Four tempos exist: Minus Tempo (Tempo 0), First Tempo (Tempo 1), Second Tempo (Tempo 2), and Third Tempo (Tempo 3).

| Tempo Type | Characteristics (Relationship between Set and Takeoff) | Set Trajectory | Advantage against Read Block |

| Minus Tempo (Tempo 0) | Takeoff before the setter contacts the ball (The attacker waits in the air). | Direct Delivery | Advantage (Hits before block completes) |

| First Tempo (Tempo 1) | Takeoff simultaneously with or immediately after the setter contacts the ball. | In-Direct Delivery Tendency | Advantage (Hits simultaneously with or slightly before block) |

| Second Tempo (Tempo 2) | Takeoff after the set ball reaches its peak height. Attacker adjusts approach and jump. | In-Direct Delivery | Neutral (Blockers have time to adjust) |

| Third Tempo (Tempo 3) | Takeoff long after the set ball has peaked (High ball). | In-Direct Delivery | Disadvantage (Blockers can easily form a triple block) |

The core determinant of Tempo is the interval between the Set and the Takeoff. However, I have to emphasize the fundamental importance of a sufficient approach. This is because, especially in Minus and First Tempos, the urge to hit faster than the opponent’s read block can often lead to a shortened approach, sacrificing the attacker’s potential height and power.

Set Trajectory: Direct vs. In-Direct Delivery

- Direct Delivery:

A straight-line trajectory intended to deliver the ball directly to the attacker’s hitting point. This often sacrifices the attacker’s height because the ball is hit before or near the apex of its arc. - In-Direct Delivery:

A parabolic trajectory that allows the attacker to hit the ball near the apex of its arc. This maximizes the attacker’s height and course width.

| Tempo Type | Set Trajectory | Implication |

| Minus Tempo (Tempo 0) | Direct Delivery | The attacker jumps before the set and waits in the air, limiting the time available. Therefore, the trajectory tends to be linear. Hitting before the read block completes is the priority. |

| First Tempo (Tempo 1) | In-Direct Delivery Tendency | The Takeoff is simultaneous with or slightly after the set, allowing the attacker to hit before or simultaneously with the read block’s takeoff. This timing, combined with an In-Direct Delivery, maximizes the attacker’s height and course range—the optimal balance between speed and power. |

| Second Tempo (Tempo 2) Third Tempo (Tempo 3) | In-Direct Delivery | The attacker has time to approach and jump after reading the set, making the In-Direct Delivery the standard trajectory to maximize power and height. |

Synchronized Attack: The Counter-Tactic

With a better understanding of Tempo and Slot, we can revisit the Synchronized Attack tactic designed to counter the Read Block:

The Synchronized Attack tactic involves four attackers (excluding the setter and Libero) participating simultaneously using the First Tempo (Tempo 1) from different Slots (spatial positions).

The essence of the Synchronized Attack is threefold:

- Numerical Advantage:

Securing a 4-on-3 advantage against the three opposing front-row players. - Relative Speed, Height, and Power:

Ensuring all attackers participate with the First Tempo to maximize their relative speed and individual hitting ability (height/power). - Front Blocker Separation:

Utilizing the maximum difference in Slots (positional difference) to force the opposing front blockers to separate and make difficult decisions.

This combination makes the Synchronized Attack an incredibly effective counter-tactic to the standardized Read Block system.

Lessons Learned from the Concept of Tempo

This article focused on the concept of Tempo, tracing its origins and historical shifts through the lens of rules and tactics. What started as a simple intention to organize the concept of Tempo into a table evolved into a lengthy process, revealing the necessity of understanding the word’s etymology and history to grasp its essence.

This journey has deepened my respect for other volleyball terms and an awe for the predecessors who “gave birth” to them.

The widespread introduction of volleyball terms through “Haikyu!!” has profoundly impacted the Japanese volleyball community.

I sincerely hope that these terms are not only spread widely but are also deepened in their understanding. The weeks spent writing this article have been entirely fulfilling, reinforcing my love for volleyball through the discussions and insights gained along the way.

#VolleyballCoaching #YouthVolleyball #VolleyballTactics #SystemVolleyball #TempoConcept #SlotConcept #ReadBlock #SynchronizedAttack #TacticalEvolution #RulesAndTactics #VolleyballHistory #CoachingTechniques #LTAD